The Evolution of Successful Parasitism of Plants by Nematodes

Rev. 10/30/2019

Pathogens or parasites that can only feed on a living host and must keep the host and its cells alive are termed biotrophic pathogens. Sedentary ecto- and endoparasitic nematodes are in this category, for example, species of Meloidogyne, Heterodera, Xiphinema, Tylenchulus, Rotylenchulus. In this context, nematodes that withdraw contents from individual cells and then move to new feeding sites are considered cell grazers.

Plant Defenses against Parasites

Most plants are resistant to most pathogens; they have highly effective immune systems. This condition is termed Innate Immunity. Host defense mechanisms against pathogens may be as extreme as programmed cell death, the hypersensitive response.

To be successful, biotrophic pathogens must suppress host defenses. The feeding site must be induced without host detection or without induction of host defenses.

Following establishment of the feeding site by sedentary nematodes, it must be maintained for up to 5 or 6 weeks to allow the nematode to achieve its reproductive potential. That time scale is much greater than that required by many bacterial and fungal pathogens of plants. Failure to establish and maintain the feeding site may prevent reproduction and therefore is catastrophic to the nematode genotype. Consequently, there is strong selection pressure on nematodes to suppress host defenses.

a. Pre-existing Defenses - Basal Resistance

Structural - cuticle, wax, wall thickness, spines that suppress penetration of cells.

Chemical - phenolic and other compounds that inhibit or kill invading organisms.

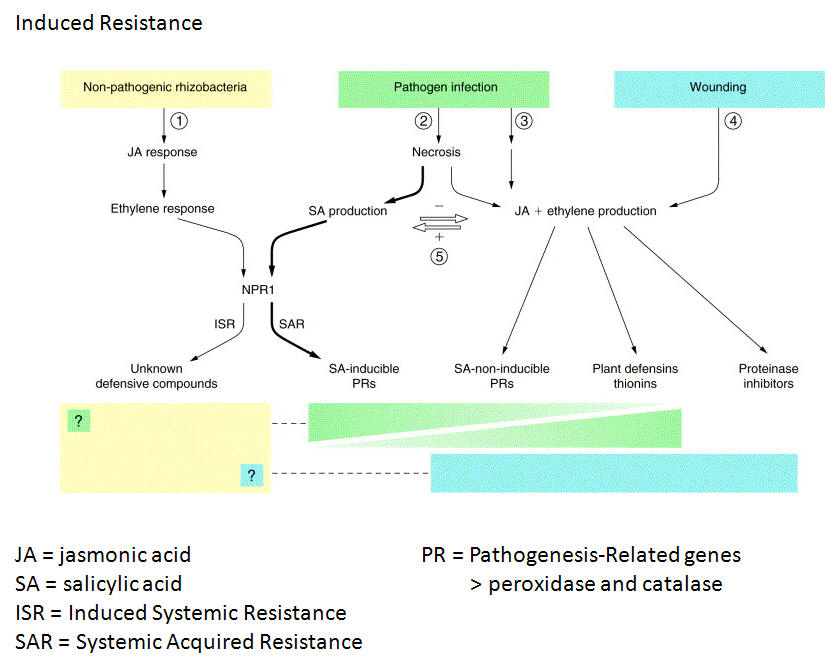

b. Systemic Induced Resistance

(i) PAMP Signals

Organisms attempting to feed on plant cells, or to invade plant tissues, betray their presence with recognizable molecular signals on their surfaces. Such signals are termed pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and are recognized by pattern recognition receptors on cell surfaces. For example, chitins in fungal cell walls are PAMPS which trigger immunity responses (pathogen-triggered immunity - PTI). The PAMP signals of nematodes are unknown; chitin is not present in the cuticle although it does occur in egg shells and perhaps in the stylet.

Plants characteristically deposit callose to strengthen cell walls at the point of invasion, including at the point of nematode stylet insertion. PAMP-triggered PTI, the first line of defense, may involve production of salicylic acid (SA) as a signal to invoke defense mechanisms including callose thickening of cell walls and initiation of active oxygen defense responses (H2O2 and superoxide) which may initiate localized programmed cell death - the hypersensitive response. Also, pathogen invasion triggers the jasmonic acid signaling pathway (JA) which stimulates production of protease inhibitors and the release of toxins.

(ii) DAMP Signals

Another set of signals that may trigger PTI responses in plants are cell-degradation products resulting from damage caused by the invasion, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).

Effector Suppression of Plant Defenses and PTI

Invading bacteria and fungi, and probably nematodes, release effector molecules into plant cells to suppress PTI and render the plant susceptible to infection or invasion - Effector Triggered Susceptibiity (ETS).

PAMP-triggered PTI, the first line of defense to invasion, may involve production of salicylic acid (SA) as a signal to invoke defense mechanisms. In that case, successful nematode infections would require suppression of SA production, reduction of callose thickening of cell walls and suppression of active oxygen defense responses (H2O2, superoxide), and the hypersensitive response of localized programmed cell death.

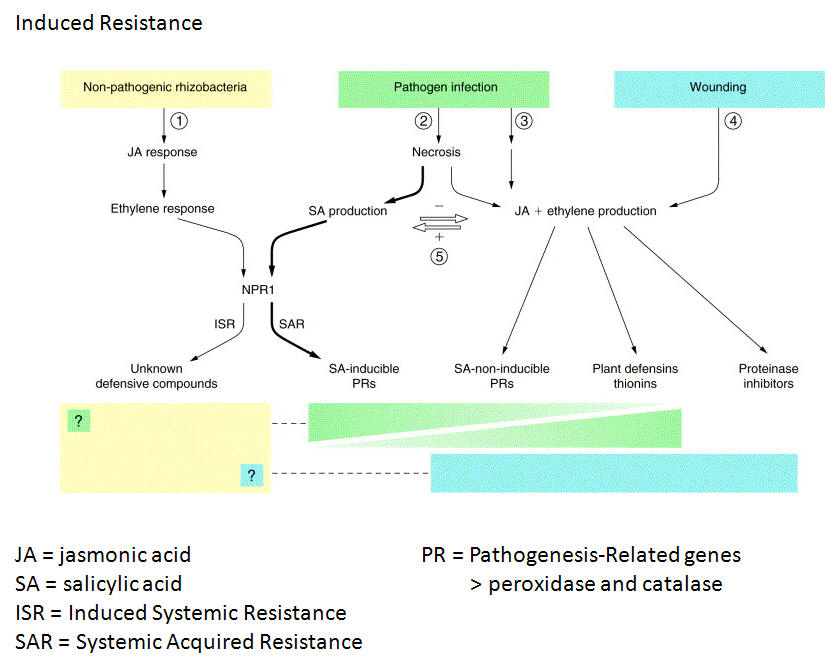

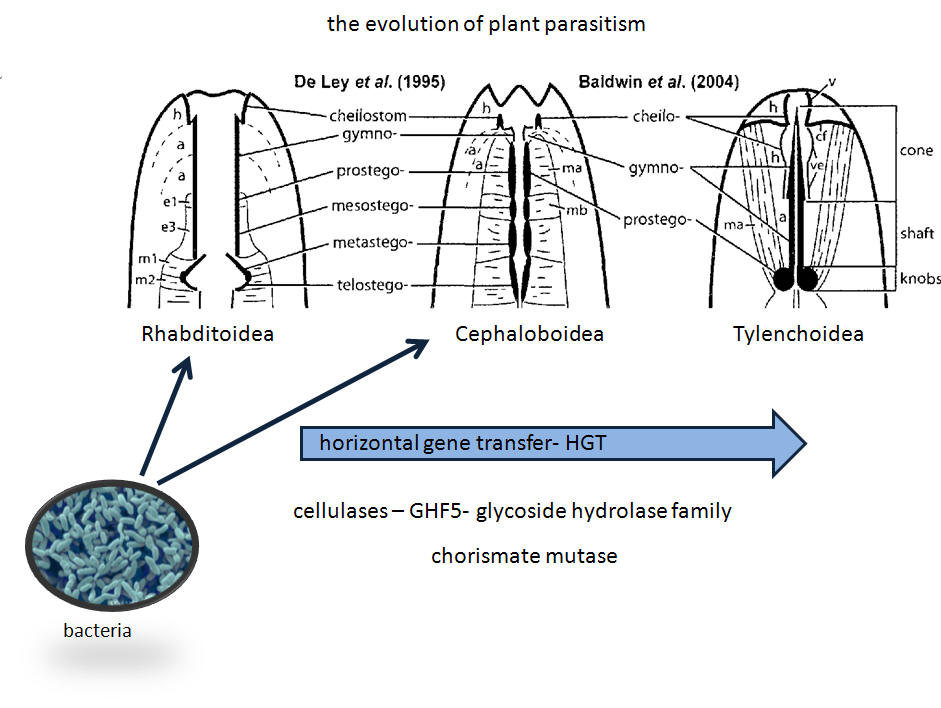

SA signaling is possibly disrupted by chorismate mutase produced in the esophageal glands of nematodes. In the PTI signaling pathway, chorismate is converted to salicylic acid. Chorismate mutase from the nematode reduces chorismate and thus SA, so defense mechanisms are not triggered. Incidentally, like cellulases, chorismate mutase is an example of horizontal gene transfer from bacteria. Nematodes are the only metazoan with the enzyme.

An alternative mechanism of PTI suppression by nematodes is the production of effectors which cause ubiquitin to attach to plant signal proteins and thus reduce their levels and effectiveness in triggering PTI responses.

The Mi8D05 parasitism gene of Meloidogyne incognita produces an effector protein important role in the interaction with host plants. Mi8D05 peaks in expression in the parasitic J2 stage of M. incognita when induction and early formation of giant-cells occurs. The gene encodes a protein of 382 amino acids which is located in the subventral gland cells of M. incognita J2 and is probably secreted into host plant tissues. RNA interference tests using a double-stranded RNA complementary to Mi8D05 reduced by 90% M. incognita infection of Arabidopsis (Xue et al., 2013).

Note: GHF5 glycoside hydrolases are expressed in Aphelenchoides fragariae when feeding on plant tissue; the expression decreases x1800 when transferred to fungus for several generations (Fu et al., 2012).

The Evolutionary Response: Effector-triggered Immunity

The evolution of effector suppression of PTI has resulted in evolution of immune receptors, with a nucleotide-binding domain and a leucine-rich domain (NB-LRR), in plants that recognize the effector molecules and activate effector-triggered immunity (ETI).

However, successful pathogens have evolved next-generation effectors that suppress ETI. Plants have responded with more specific ETIs and the evolutionary treadmill continues.

PTI responses to PAMPs and DAMPs are relatively general in their effect but higher level ETIs are progressively more specific to individual pathogens.

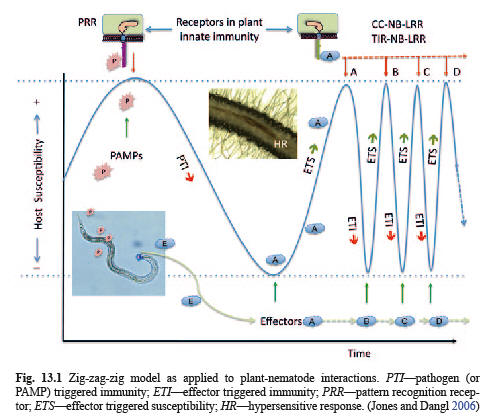

The cyclical evolutionary process of plant-nematode interactions with regard to plant immunity and susceptibility is depicted by the zig-zag-zig model (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Initially PAMPs trigger PTI which reduces susceptibility. Then nematodes develop effectors that suppress PTI and plants evolve immunity responses to the effectors.

Mechanisms of Effector-triggered Immunity (ETI) and Effector-triggered Susceptibility (ETS)

In effect, the sources of specific ETIs are resistance genes. The hypersensitive response of cells to the activated ETI effectively disrupts the feeding and development of sedentary endoparasitic nematode species.

The Mi gene of tomato codes for receptors to the effector molecules introduced by root-knot nematodes that would otherwise suppress plant defenses and facilitate the development of feeding sites.

However, although they are known for some other pathogens, the nematode effector ETS molecules that suppress plant defenses and facilitate the development of feeding sites are still being determined. They are the focus of several active research programs.

Examples include:

The Hg30C02 effector protein of Heterodera glycines which may be involved in active suppression of host defenses. Hg30C02 specifically interacts with a plant ß-1,3-endoglucanase (Hamamouch et al., 2012).

The Mi8D05 parasitism gene of Meloidogyne incognita produces an effector protein important role in the interaction with host plants. Mi8D05 peaks in expression in the parasitic J2 stage of M. incognita when induction and early formation of giant-cells occurs. The gene encodes a protein of 382 amino acids which is located in the subventral gland cells of M. incognita J2 and is probably secreted into host plant tissues. RNA interference tests using a double-stranded RNA complementary to Mi8D05 reduced by 90% M. incognita infection of Arabidopsis (Xue et al., 2013).

Suppression and Avoidance of Host Defenses by Nematodes

Nematodes are protected by the cuticle and surface coat. The surface coat of the cuticle, consisting of lipid and protein molecules is shed as the nematode moves, shedding bacteria but also confusing the plants as to whereabouts of the nematode.

Glutathione peroxidases on surface coats of nematodes reduce active oxygen plant defenses.

Many plant-parasitic nematodes produce glutathione S tranferases that detoxify endogenous toxic molecules.

Nematodes produce superoxide dismutase that breaks down active oxygen plant defenses.

References

Hamamouch, N., Li, C., Hewezi, T., Baum, T.J., Mitchum, M.G., Hussey, R.S., Vodkin, L.O., Davis, E.L. 2012. The interaction of the novel Hg30C02 cyst nematode effector protein with a plant b-1,3-endoglucanase may suppress host defence to promote parasitism. Journal of Experimental Botany.

Huang, G., Dong, R., Allen, R., Davis, E.L., Baum,

T.J., Hussey, R.S. 2005. Two chorismate mutase genes from the root-knot nematode

Meloidogyne incognita.

Molecular Plant

Pathology 6:23-30.

Jones, J.D.G, Dangl, J.L. 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444:323-329.

Jones, J.T., Gheysen, G. and Fenoll, C. (eds) 2011. Genomics and molecular genetics of plant-nematode interactions. Springer Academic Publishers.

Jones, J.T. 2012. Lectures in the EUMAINE program, University of Ghent.

Jones, J.T., Furlanetto, C., Bakker, E., Banks, B., Blok, V., Chen, Q., Phillips, M. and Prior, A. 2003. Characterization of a chorismate mutase from the potato cyst nematode Globodera pallida. Molecular Plant Pathology 4:43–50.

Lambert, K.N., Allen, K.D. and Sussex, I.M. 1999.

Cloning and characterization of an esophageal-gland-specific chorismate mutase

from the phytoparasitic nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Molecular

Plant-Microbe Interactions 12:328–336.

Smant, G., Jones, J. 2011. Suppression of plant defences by nematodes. Chapter 13, pp 273-286. In Jones, J., Gheysen, G., Fenoll, C. (eds). Genomics and Molecular Genetics of Plant-Nematode Interactions. Springer, NY.